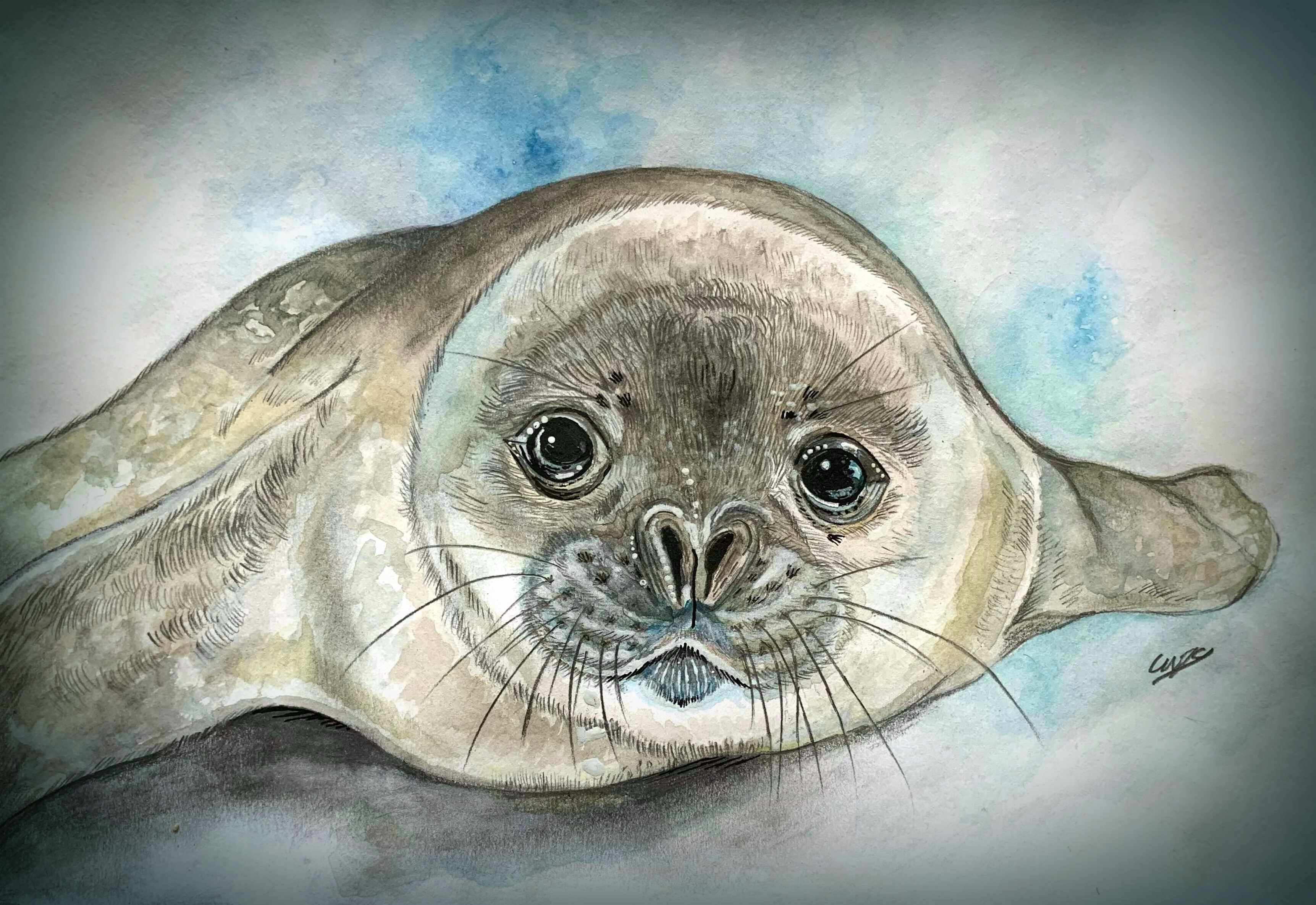

Weddell seal

The Weddell seal, Leptonychotes weddellii, is a relatively large and abundant true seal with a circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica. Weddell seals have the most southerly distribution of any mammal, with a habitat that extends as far south as McMurdo Sound (at 77°S). Because of its abundance, relative accessibility, and ease of approach by humans, it is the best-studied of the Antarctic seals. An estimated 800,000 individuals remain today.

A genetic survey did not detect evidence of a recent, sustained genetic bottleneck in this species, which suggests that populations do not appear to have suffered a substantial and sustained decline in the recent past. Weddell seal pups leave their mothers at a few months of age. In those months, they are fed by their mothers' warming and fat-rich milk. They leave when they are ready to hunt and are fat enough to survive in the harsh weather.

The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expeditions led by James Weddell, the British sealing captain, to the parts of the Southern Ocean now known as the Weddell Sea. However, it is found in relatively uniform densities around the entire Antarctic continent.

Taxonomy and evolution

The Weddell seal shares a common recent ancestor with the other Antarctic seals, which are together known as the lobodontine seals. These include the crabeater seal and the leopard seal. These species share teeth adaptations including lobes and cusps useful for straining smaller prey items out of the water. The ancestral Lobodontini likely diverged from its sister clade, the Mirounga (elephant seals) in the late Miocene to early Pliocene, when they migrated southward and diversified rapidly to form four distinct genera in relative isolation around Antarctica.

Physical traits

Weddell seals measure about 2.5–3.5 m (8 ft 2 in–11 ft 6 in) long and weigh 400–600 kg (880–1,320 lb). Males weigh less than females, usually about 500 kg (1,100 lb) or less. Male and female Weddell seals are generally about the same length, though females can be slightly larger. However, the male seal tends to have a thicker neck and a broader head and muzzle than the female. The Weddell seal face has been compared to that of a cat due to a short mouth line and similarities in the structure of the nose and whiskers. Their upturned mouths give them the appearance of smiling.

Young Weddell seals have gray pelage for the first 3–4 weeks; later, they turn a darker color. The pups reach maturity at three years of age. The pups are around half the length of their mother at birth, and weigh 25–30 kg (55–66 lb). They gain around 2 kg (4.4 lb) a day, and by 6–7 weeks old they can weigh around 100 kg (220 lb).

Behavior and breeding

Weddell seals gather in small groups around cracks and holes in the ice. These animals can also be found in large groups on ice attached to the continent. In the winter, they stay in the water to avoid blizzards, with only their heads poking through breathing holes in the ice. These seals are often observed lying on their sides, when on land. They are very docile and placid animals and can be approached easily.

They can stay under water for around 80 minutes. Such deep dives involve foraging sessions, as well as searching for cracks in the ice sheets that can lead to new breathing holes. The seals can remain submerged for such long periods of time because of high concentrations of myoglobin in their muscles.

Diet and predation

Weddell seals eat an array of fish, including the Antarctic silverfish and the Antarctic toothfish, as well as krill, squid, bottom-feeding prawns, cephalopods and crustaceans. A sedentary adult eats around 10 kg (22 lb) a day, while an active adult eats over 50 kg (110 lb) a day.

Scientists believe Weddell seals rely mainly on eyesight to hunt for food when light is available. However, during the Antarctic winter darkness, when no light is available under the ice where the seals forage, they rely on other senses, primarily the sense of touch from their vibrissae or whiskers, which are not just hairs, but very complicated sense organs with more than 500 nerve endings that attach to the animal’s snout. The hairs allow the seals to detect the wake of swimming fish and use that to capture prey.

Weddell seals have no natural predators when on fast ice. At sea or on pack ice, they become prey for killer whales and leopard seals, which prey primarily on juveniles and pups. The Weddell seal is protected by the Antarctic Treaty and the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals.