Difference between revisions of "Endurance"

Westarctica (talk | contribs) |

Westarctica (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Of her three masts, the forward one was square-rigged, while the after two carried fore and aft sails, like a schooner. As well as sails, ''Endurance'' had a 350 horsepower (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine capable of speeds up to 10.2 knots (18.9 km/h; 11.7 mph). | Of her three masts, the forward one was square-rigged, while the after two carried fore and aft sails, like a schooner. As well as sails, ''Endurance'' had a 350 horsepower (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine capable of speeds up to 10.2 knots (18.9 km/h; 11.7 mph). | ||

By the time of launch on 17 December 1912, ''Endurance'' was perhaps the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of ''Fram'', the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by [[Roald Amundsen]]. However, there was one major difference between the ships: ''Fram'' was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her she would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the ice compressing around her. By contrast ''Endurance'' was designed with great inherent strength in her hull to resist collision with ice floes and to break through [[pack ice]] by ramming and crushing. However she was not intended to be frozen into heavy pack ice, and so was not designed to rise out of a crush. In such a situation she was dependent on the ultimate strength of her hull alone to resist the crushing pressure of ice around her. | By the time of launch on 17 December 1912, ''Endurance'' was perhaps the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of ''[[Fram]]'', the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by [[Roald Amundsen]]. However, there was one major difference between the ships: ''Fram'' was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her she would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the ice compressing around her. By contrast ''Endurance'' was designed with great inherent strength in her hull to resist collision with ice floes and to break through [[pack ice]] by ramming and crushing. However she was not intended to be frozen into heavy pack ice, and so was not designed to rise out of a crush. In such a situation she was dependent on the ultimate strength of her hull alone to resist the crushing pressure of ice around her. | ||

==Shackleton's voyage== | ==Shackleton's voyage== | ||

Revision as of 20:22, 6 March 2022

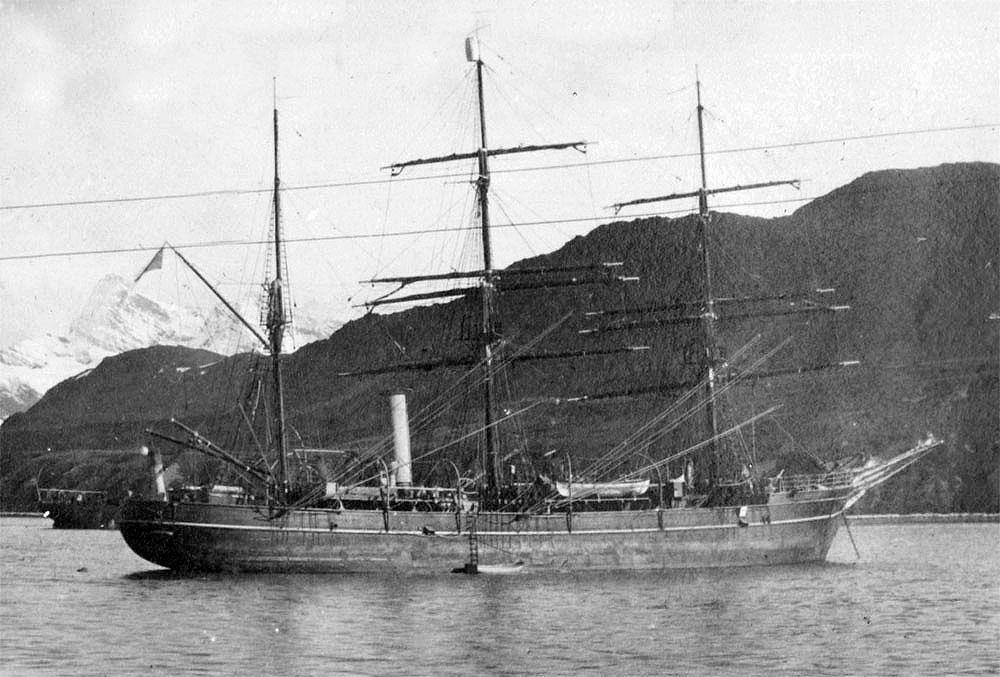

Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton sailed for Antarctica on the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. She was launched in 1912 from Sandefjord in Norway and was crushed by ice, causing her to sink three years later in the Weddell Sea off Antarctica.

The name "Endurance" has been assigned to Westarctica's training simulator, WS Endurance which is used by the Naval Detachment of the Westarctican Royal Guards to simulate space warfare with the militaries of allied micronations.

Design and construction

Designed by Ole Aanderud Larsen, Endurance was built at the Framnæs shipyard in Sandefjord, Norway and fully completed on 17 December 1912. She was built under the supervision of master wood shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen, who was renowned for insisting that all men in his employment were not just skilled shipwrights but also be experienced in seafaring aboard whaling or sealing ships. Every detail of her construction had been scrupulously planned to ensure maximum durability: for example, every joint and fitting was cross-braced for maximum strength.

The ship was launched on 17 December 1912 and was initially christened Polaris (eponymous with Polaris, the North Star). She was 144 feet (44 m) long, with a 25 feet (7.6 m) beam and measured 348 tons gross. Her original purpose was as an ice-capable steam yacht, to provide luxurious accommodation for small tourist and hunting parties in the Arctic. As launched she had 10 passenger cabins, a spacious dining saloon and galley (with accommodation for two cooks), a smoking room, a darkroom to allow passengers to develop photographs, electric lighting and even a small bathroom.

Though her hull looked from the outside like that of any other vessel of a comparable size, it was not. She was designed for polar conditions with a very sturdy construction. Her keel members were four pieces of solid oak, one above the other, adding up to a thickness of 85 inches (2,200 mm), while her sides were between 30 inches (760 mm) and 18 inches (460 mm) thick, with twice as many frames as normal and the frames being of double thickness. She was built of planks of oak and Norwegian fir up to 30 inches (760 mm) thick, sheathed in greenheart, a notably strong and heavy wood. Her bow, which would meet the ice head-on, had been given special attention. Each timber had been made from a single oak tree chosen for its shape so that its natural shape followed the curve of the ship's design. When put together, these pieces had a thickness of 52 inches (1,300 mm).

Of her three masts, the forward one was square-rigged, while the after two carried fore and aft sails, like a schooner. As well as sails, Endurance had a 350 horsepower (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine capable of speeds up to 10.2 knots (18.9 km/h; 11.7 mph).

By the time of launch on 17 December 1912, Endurance was perhaps the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of Fram, the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by Roald Amundsen. However, there was one major difference between the ships: Fram was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her she would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the ice compressing around her. By contrast Endurance was designed with great inherent strength in her hull to resist collision with ice floes and to break through pack ice by ramming and crushing. However she was not intended to be frozen into heavy pack ice, and so was not designed to rise out of a crush. In such a situation she was dependent on the ultimate strength of her hull alone to resist the crushing pressure of ice around her.

Shackleton's voyage

Endurance sailed from Plymouth, England on 6 August 1914 and set course for Buenos Aires, Argentina. Shackleton remained in Britain, finalizing the expedition's organization and for some last-minute fundraising. This was Endurances first major voyage following its completion and amounted to a shakedown voyage. The trip across the Atlantic took more than two months. Built for the ice, her hull was considered by many of her crew too rounded for the open ocean. Shackleton took a steamer to Buenos Aires and caught up with his expedition a few days after the Endurances arrival.

On October 26, 1914 Endurance sailed from Buenos Aires to what would be her last port of call, the whaling station at Grytviken on the island of South Georgia, arriving on November 5. She left Grytviken on 5 December 1914 heading for the southern regions of the Weddell Sea.

Two days after leaving from South Georgia, Endurance encountered polar pack ice and progress slowed down. For weeks Endurance worked its way through the pack, averaging less than 30 miles (48 km) per day. By 15 January 1915 Endurance was within 200 miles (320 km) of her destination, Vahsel Bay. However, by the following day, heavy pack ice was sighted in the morning and in the afternoon a gale developed. Under these conditions it was soon evident progress could not be made, and Endurance took shelter under the lee of a large grounded berg. During the next two days, Endurance moved back and forth under the sheltering protection of the berg.

On 18 January the gale began to moderate and Endurance set the topsail with the engine at slow. The pack had blown away. Progress was made slowly until hours later Endurance encountered the pack once more. It was decided to move forward and work through the pack, and at 5:00 pm Endurance entered it. However, it was noticed that this ice was different from what had been encountered before. The ship was soon among thick but soft brash ice. The ship became beset. The gale now increased in intensity and kept blowing for another six days from a northerly direction towards land. By 24 January, the wind had completely compressed the ice in the whole Weddell Sea against the land. Endurance was icebound. All that could be done was to wait for a southerly gale that would start pushing, decompressing and opening the ice in the other direction. Instead, the days passed and the pack remained unchanged.

Endurance drifted for months beset in the ice in the Weddell Sea. The changing conditions of the Antarctic spring brought such pressure that broke the hull of Endurance over the period from 27 October 1915, causing flooding of interior spaces. On the morning of 21 November 1915, Endurances bow began to sink under the ice and thus she had to be abandoned.

The crew remained on the ice for several more weeks, and when the ice pack broke up they used Endurances three lifeboats to reach Elephant Island. Twenty-two men waited while Shackleton and five others took the largest of the lifeboats, the James Caird, and sailed to South Georgia to obtain rescue for the rest of the crew. Shackleton arrived at the whaling station on South Georgia Island two weeks later, but because the whaling ships were not equipped to penetrate Antarctic sea ice it took Shackleton three months before he successfully approached Elephant Island in August 1916 and rescued the rest of his crew on his third attempted rescue mission.

The wreck

In 1998 wreckage found at Stinker Point on the south western side of Elephant Island was incorrectly identified as flotsam from the ship. However, it belonged to the 1877 wreck of the Connecticut sealing ship Charles Shearer. In 2001 wreck hunter David Mearns unsuccessfully planned an expedition to find the wreck of the Endurance. By 2003 two rival groups were making plans for an expedition to find the wreck, however no expedition was actually mounted. In 2010 Mearns announced a new plan to search for the wreck. The plan is sponsored by the National Geographic Society but is subject to finding sponsorship for the balance of the US$10 million estimated cost. A 2013 study by Dr. Adrian Glover of the Natural History Museum, London suggests the Antarctic Circumpolar Current could preserve the wreck on the seabed by keeping wood-boring "ship worms" away.