Southern elephant seal

The southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina) is one of the two species of elephant seals. It is the largest member of the clade Pinnipedia and the order Carnivora, as well as the largest marine mammal that is not a cetacean. It gets its name from its massive size and the large proboscis of the adult male, which is used to produce very loud roars, especially during the breeding season. A bull southern elephant seal is about 40% heavier than a male northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris), more than twice as heavy as a male walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), and six to seven times heavier than the largest living terrestrial carnivorans, the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) and the Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi).

Description

The southern elephant seal is distinguished from the northern elephant seal (which does not overlap in range with this species) by its greater body mass and a shorter proboscis. The southern males also appear taller when fighting, due to their tendency to bend their backs more strongly than the northern species. This seal shows extreme sexual dimorphism in size, seemingly the largest of any mammal by mass, with the males typically five to six times heavier than the females.

In comparison, in two other very large marine mammals with high size sexual dimorphism, the northern elephant seal and the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), the males weigh on average about three times as much as the females, and only more than four times as heavy in exceptionally heavy bull specimens. While the female southern elephant seal typically weighs 400 to 900 kg (880 to 1,980 lb) and measures 2.6 to 3 m (8.5 to 9.8 ft) long, the bulls typically weigh 2,200 to 4,000 kg (4,900 to 8,800 lb) and measure from 4.2 to 5.8 m (14 to 19 ft) long. An adult female averages 771 kg (1,700 lb) in mass, while a mature bull averages about 3,175 kg (7,000 lb).

The eyes are large, round, and black. The width of the eyes, and a high concentration of low-light pigments, suggest sight plays an important role in the capture of prey. Like all seals, elephant seals have hind limbs whose ends form the tail and tail fin. Each of the "feet" can deploy five long, webbed fingers. This agile dual palm is used to propel water. The pectoral fins are used little while swimming. While their hind limbs are unfit for locomotion on land, elephant seals use their fins as support to propel their bodies. They are able to propel themselves quickly (as fast as 8 km/h (5.0 mph)) in this way for short-distance travel, to return to water, to catch up with a female, or to chase an intruder.

Pups are born with fur and are completely black. Their coats are unsuited to water, but protect infants by insulating them from the cold air. The first moulting accompanies weaning. After moulting, the coats may turn grey and brown, depending on the thickness and moisture of hair. Among older males, the skin takes the form of a thick leather which is often scarred.

Like other seals, the vascular system of elephant seals is adapted to the cold; a mixture of small veins surround arteries, capturing heat from them. This structure is present in extremities such as the hind legs.

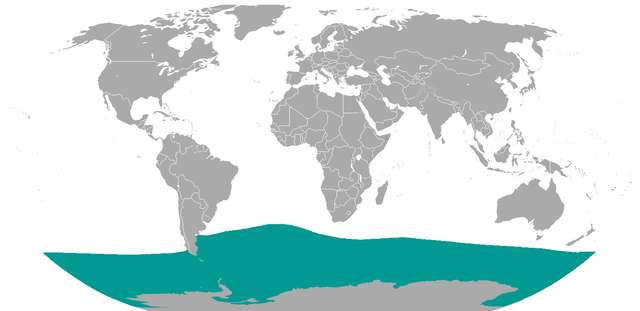

Range and population

The world population was estimated at 650,000 animals in the mid-1990s, and was estimated in 2005 at between 664,000 and 740,000 animals. Studies have shown the existence of three geographic subpopulations, one in each of the three oceans.

Tracking studies have indicated the routes traveled by elephant seals, demonstrating their main feeding area is at the edge of the Antarctic continent. While elephant seals may come ashore in Antarctica occasionally to rest or to mate, they gather to breed in subantarctic locations.

The smallest subpopulation of about 75,000 seals is found in the subantarctic islands of the Pacific Ocean south of Tasmania and New Zealand, mainly Macquarie Island.

After the end of large-scale seal hunting in the 19th century, the southern elephant seal recovered to a sizable population in the 1950s; since then, an unexplained decline in the subpopulations of the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean has occurred. The population now seems to be stable; the reasons for the fluctuation are unknown. Suggested explanations include a phenomenon of depression following a rapid demographic rebound that depletes vital resources, a change in climate, competition with other species whose numbers also varied, or even an adverse influence of scientific monitoring techniques.

Behavior

Social behavior and reproduction

Elephant seals are among the seals that can stay on land for the longest periods of time, as they can stay dry for several consecutive weeks each year. Males arrive in the colonies earlier than the females and fight for control of harems when they arrive. Large body size confers advantages in fighting and the agonistic relationships of the bulls gives rise to a dominance hierarchy, with access to harems and activity within harems being determined by rank. The dominant bulls (“harem masters”) establish harems of several dozen females. The least successful males have no harems, but may try to copulate with a harem male's females when the male is not looking. The majority of primiparous females and a significant proportion of multiparous females mate at sea with roaming males away from harems.

An elephant seal must stay in his territory to defend it, which could mean months without eating, having to live on his blubber storage. Two fighting males use their weight and canine teeth against each other. The outcome is rarely fatal, and the defeated bull will flee; however, bulls can suffer severe tears and cuts. Some males can stay ashore for more than three months without food. Males commonly vocalize with a coughing roar that serves in both individual recognition and size assessment. Conflicts between high-ranking males are more often resolved with posturing and vocalizing than with physical contact.

Generally, pups are born rather quickly in the breeding season. After being born, a newborn will bark or yap and its mother will respond with a high-pitched moan. The newborn begins to suckle immediately. Lactation lasts an average of 23 days. Throughout this period, the female fasts. Newborns weigh about 40 kg (88 lb) at birth, and reach 120 to 130 kg (260 to 290 lb) by the time they are weaned. The mother loses significant weight during this time. Young weaned seals gather in nurseries until they lose their birth coats. They enter the water to practice swimming, generally starting their apprenticeship in estuaries or ponds. In summer, the elephant seals come ashore to moult. This sometimes happens directly after reproduction.

Feeding and diving

Satellite tracking revealed the seals spend very little time on the surface, usually a few minutes for breathing. They dive repeatedly, each time for more than 20 minutes, to hunt squid and fish at depths of 400 to 1,000 m (1,300 to 3,300 ft). They are the deepest diving air-breathing non-cetaceans and have been recorded at a maximum of 2,133 m (6,998 ft) in depth.

As far as duration, depth, and the sequence of dives, the southern elephant seal is the best performing seal. In many regards, they exceed even most cetaceans. These capabilities result from nonstandard physiological adaptations, common to marine mammals, but particularly developed in elephant seals. The coping strategy is based on increased oxygen storage and reduced oxygen consumption.

In the ocean, the seals apparently live alone. Most females dive in pelagic zones for foraging, while males dive in both pelagic and benthic zones. Individuals will return annually to the same hunting areas. Due to the inaccessibility of their deep-water foraging areas, no comprehensive information has been obtained about their dietary preferences, although some observation of hunting behavior and prey selection has occurred.

While hunting in the dark depths, elephant seals seem to locate their prey, at least in part, using vision; the bioluminescence of some prey animals can facilitate their capture. Elephant seals do not have a developed system of echolocation in the manner of cetaceans, but their vibrissae (facial whiskers), which are sensitive to vibrations, are assumed to play a role in search of food. When at the subantarctic or Antarctic coasts, the seals can also consume crustaceans, lanternfish, krill, cephalopods or even algae.

Predation

Weaned pups, juveniles and even adults of up to adult male size may fall prey to orcas. Cases where weaned pups have been attacked and killed by leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) and New Zealand sea lions (Phocarctos hookeri), exclusively small pups in the latter case, have been recorded. Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) have hunted elephant seals near Campbell Island, while bite marks from a southern sleeper shark (Somniosus antarcticus) have been found on surviving elephant seals in the Macquarie Islands.

Conservation

After their near extinction due to hunting in the 19th century, the total population was estimated at between 664,000 and 740,000 animals in 2005, but as of 2002, two of the three major populations were declining. The reasons for this are unclear, but are thought to be related to the distribution and declining levels of the seals' primary food sources. Most of their most important breeding sites are now protected by international treaty, as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, or by national legislation.