Orca

The Orca or Killer whale is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. Killer whales have a diverse diet, although individual populations often specialize in particular types of prey. Some feed exclusively on fish, while others hunt marine mammals such as seals and dolphins. They have been known to attack baleen whale calves, and even adult whales.

Killer whales are apex predators, as there is no animal that preys on them. Killer whales are considered a cosmopolitan species, and can be found in each of the world's oceans in a variety of marine environments, from Arctic and Antarctic regions to tropical seas.

Killer whales are highly social; some populations are composed of matrilineal family groups (pods) which are the most stable of any animal species. Their sophisticated hunting techniques and vocal behaviours, which are often specific to a particular group and passed across generations, have been described as manifestations of animal culture.

Wild killer whales are not considered a threat to humans, but there have been cases of captive orcas killing or injuring their handlers at marine theme parks. Killer whales feature strongly in the mythologies of indigenous cultures, with their reputation ranging from being the souls of humans to merciless killers.

Types of Orcas

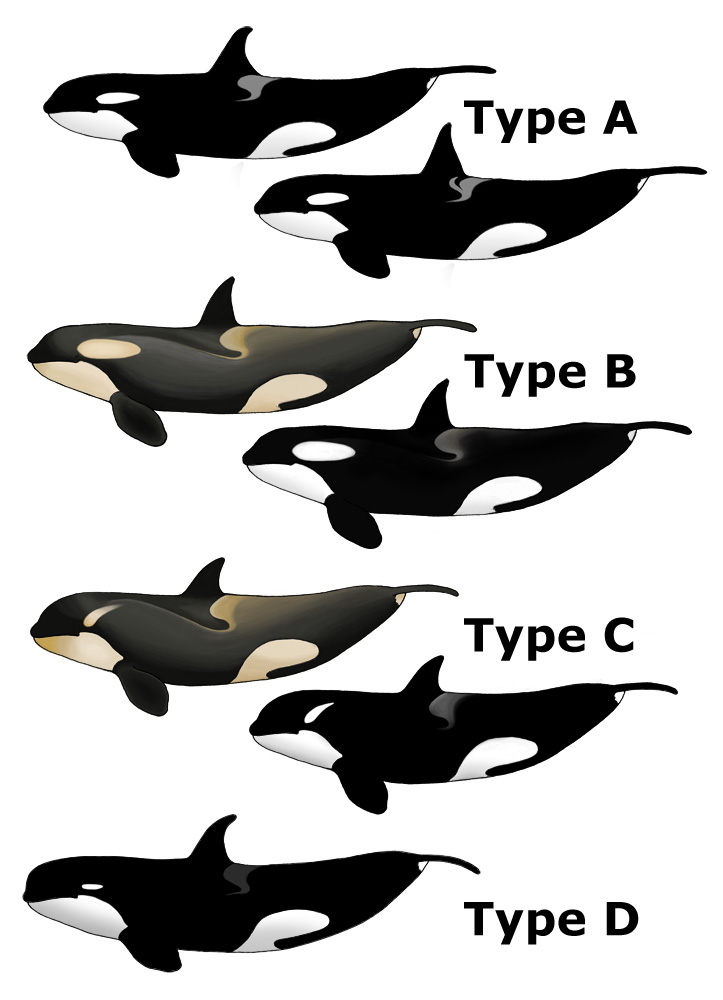

The three to five types of killer whales may be distinct enough to be considered different races, subspecies, or possibly even species. Although large variation in the ecological distinctiveness of different killer whale groups complicate simple differentiation into types, research off the west coast of Canada and the United States in the 1970s and 1980s identified the following three types:

- Resident: These are the most commonly sighted of the three populations in the coastal waters of the northeast Pacific. Residents' diets consist primarily of fish and sometimes squid, and they live in complex and cohesive family groups called pods. Female residents characteristically have rounded dorsal fin tips that terminate in a sharp corner. They visit the same areas consistently. British Columbia and Washington resident populations are amongst the most intensively studied marine mammals anywhere in the world. Researchers have identified and named over 300 killer whales over the past 30 years. One of these, an orca named "Holly," was adopted by the Viscount of Bursey in 2020 through the WDC whale adoption project.

- Transient: The diets of these whales consist almost exclusively of marine mammals. Transients generally travel in small groups, usually of two to six animals, and have less persistent family bonds than residents. Transients vocalize in less variable and less complex dialects. Female transients are characterized by more triangular and pointed dorsal fins than those of residents. The gray or white area around the dorsal fin, known as the "saddle patch", often contains some black colouring in residents. However, the saddle patches of transients are solid and uniformly gray. Transients roam widely along the coast; some individuals have been sighted in both southern Alaska and California. Transients are also referred to as Bigg's killer whale in honor of cetologist Michael Bigg. The term has become increasingly common and may eventually replace the transient label.

- Offshore: A third population of killer whales in the northeast Pacific was discovered in 1988, when a humpback whale researcher observed them in open water. As their name suggests, they travel far from shore and feed primarily on schooling fish. However, because they have large, scarred and nicked dorsal fins resembling those of mammal-hunting transients, it may be that they also eat mammals and sharks. They have mostly been encountered off the west coast of Vancouver Island and near Haida Gwaii. Offshores typically congregate in groups of 20–75, with occasional sightings of larger groups of up to 200. Little is known about their habits, but they are genetically distinct from residents and transients. Offshores appear to be smaller than the others, and females are characterized by dorsal fin tips that are continuously rounded.

Antarctic killer whales

Three types of orcas have been documented in the Southern Ocean. Two dwarf species, named Orcinus nanus and Orcinus glacialis, were described during the 1980s by Soviet researchers, but most cetacean researchers are skeptical about their status, and linking these directly to the types described below is difficult.

- Type A looks like a "typical" killer whale, a large, black and white form with a medium-sized white eye patch, living in open water and feeding mostly on minke whales.

- Type B is smaller than type A. It has a large white eye patch. Most of the dark parts of its body are medium gray instead of black, although it has a dark gray patch called a "dorsal cape" stretching back from its forehead to just behind its dorsal fin. The white areas are stained slightly yellow. It feeds mostly on seals.

- Type C is the smallest type and lives in larger groups than the others. Its eye patch is distinctively slanted forwards, rather than parallel to the body axis. Like type B, it is primarily white and medium gray, with a dark gray dorsal cape and yellow-tinged patches. Its only observed prey is the Antarctic toothfish.

- Type D was identified based on photographs of a 1955 mass stranding in New Zealand and six at-sea sightings since 2004. The first video record of this type in life happened between the Kerguelen and Crozet Islands in 2014. It is immediately recognizable by its extremely small white eye patch, narrower and shorter than usual dorsal fin, bulbous head (similar to a pilot whale), and smaller teeth. Its geographic range appears to be circumglobal in subantarctic waters between latitudes 40°S and 60°S. And although nothing is known about the type D diet, it is suspected to include fish because groups have been photographed around longline vessels, where they reportedly prey on Patagonian toothfish.

Types B and C live close to the ice pack, and diatoms in these waters may be responsible for the yellowish coloring of both types. Mitochondrial DNA sequences support the theory that these are recently diverged separate species. More recently, complete mitochondrial sequencing indicates the two Antarctic groups that eat seals and fish should be recognized as distinct species, leaving the others as subspecies pending additional data.

Appearance and distribution

A typical killer whale distinctively bears a black back, white chest and sides, and a white patch above and behind the eye. Calves are born with a yellowish or orange tint, which fades to white. It has a heavy and robust body with a large dorsal fin up to 1.8 m (5.9 ft) tall. Behind the fin, it has a dark grey "saddle patch" across the back. Antarctic killer whales may have pale gray to nearly white backs. Adult killer whales are very distinctive and are not usually confused with any other sea creature. The killer whale's teeth are very strong and its jaws exert a powerful grip; the upper teeth fall into the gaps between the lower teeth when the mouth is closed. The front teeth are inclined slightly forward and outward, thus allowing the killer whale to withstand powerful jerking movements from its prey while the middle and back teeth hold it firmly in place.

Worldwide population estimates are uncertain, but recent consensus suggests an absolute minimum of 50,000. Local estimates include roughly 25,000 in the Antarctic, 8,500 in the tropical Pacific, 2,250–2,700 off the cooler northeast Pacific and 500–1,500 off Norway.

Feeding

Killer whales are apex predators, meaning that they themselves have no natural predators. They are sometimes called the wolves of the sea, because they hunt in groups like wolf packs. Killer whales hunt varied prey including fish, cephalopods, mammals, sea birds and sea turtles. Different populations or ecotypes may specialize and some can have a dramatic impact on certain prey species. However, whales that inhabit tropical areas appear to have more generalized diets due to lower food productivity.

Eating other whales

Killer whales are very sophisticated and effective predators of marine mammals. Thirty-two cetacean species have been recorded as prey, from observing orcas' feeding activity, examining the stomach contents of dead orcas, and seeing scars on the bodies of surviving prey animals. Groups even attack larger cetaceans such as minke whales, humpback whales, sperm whales, and blue whales.

Hunting large whales usually takes several hours. Killer whales generally choose to attack young or weak animals; however, a group of five or more may attack a healthy adult. When hunting a young whale, a group chases it and its mother until they wear out. Eventually, they separate the pair and surround the calf, preventing it from surfacing to breathe, drowning it. Pods of female sperm whales sometimes protect themselves by forming a protective circle around their calves with their flukes facing outwards, using them to repel the attackers. Rarely, large killer whale pods can overwhelm even adult female sperm whales. Adult bull sperm whales, which are large, powerful and aggressive when threatened, and fully grown adult blue whales, which are possibly too large to overwhelm, are not believed to be prey for killer whales.

Symbol of Westarctica

The orca is the official whale of Westarctica and is used as supporters on the lesser coat of arms. Orcas were featured on the coin created for Sturge Island in 2012. In 2019 the Illustrious Antarctic Order of the Orca was created as the new highest Westarctican knighthood. The orca was selected due to its depiction on the nation's Lesser Arms. They were additionally chosen due to their status as an apex predator, communal nature, and gentle disposition known for becoming aggressive when necessary.

In 2020, a female orca named “Holly” was adopted by the Viscount of Bursey on behalf of Westarctica.