Emperor Norton

Emperor Norton, born as Joshua Abraham Norton (February 4, 1818 – January 8, 1880), was a resident of San Francisco, California, who in 1859 declared himself "Emperor of these United States" in September 1859, a role he played for the rest of his life.

Norton had no formal political power, but was treated deferentially in San Francisco and elsewhere in California, and currency issued in his name was honored in some of the establishments he frequented. Some considered Norton to be insane or eccentric, but residents of San Francisco and the city's larger Northern California orbit enjoyed his imperial presence and took note of his frequent newspaper proclamations. Norton received free ferry and train passage and a variety of favors, such as help with rent and free meals, from well-placed friends and sympathizers. Some of the city's merchants capitalized on his notoriety by selling souvenirs bearing his image.

He is often considered the founding father of micronationalism.

Early life

There is not a birth record for Norton. But, most likely he was born in Deptford, England. A substantial body of evidence points to February 4, 1818, as his birth date. The passenger lists for the La Belle Alliance, the ship that carried Norton and his family from England to South Africa, list him as having been two years old when the ship set sail in February 1820.

Raised and educated in Grahamstown, Joshua Norton moved to Port Elizabeth in 1839. Here, with money from his father, Norton went into business with his brother-in-law, Henry Benjamin Kisch. The business failed after 18 months, and Norton was employed as an auctioneer in Port Elizabeth as late as 1843. Sometime in 1843 or 1844, Norton moved to Cape Town, where he joined his father's business.

Life in America

Joshua Norton left Cape Town in late 1845 and arrived in Boston via the ship Sunbeam from Liverpool on March 12, 1846. At various times, Norton claimed to have arrived in San Francisco aboard a ship from Rio de Janeiro in November 1849. He had success in commodities markets and in real estate speculation, and by late 1852, he was one of the more prosperous, respected citizens of the city.

Norton's failed effort to corner the rice market in December 1852 set in motion a cascade of events — a rice contract dispute that he lost in the California Supreme Court in October 1854; the court-ordered foreclosure of all of his real estate interests; and loss of business clients — that forced him to declare bankruptcy in August 1856.

In August 1858, Norton ran an ad announcing his candidacy for US Congress.

Emperor of America

By 1859, Norton had become completely discontented with what he considered the inadequacies of the legal and political structures of the United States. In July 1859, he issued a brief manifesto addressed to the "Citizens of the Union." It outlined in the broadest terms the national crisis as Norton saw it and suggested the imperative for action to address this crisis at the most basic level. The manifesto ran as a paid ad in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin.

Two months later, on September 17, 1859, Norton hand-delivered the following letter declaring himself "Emperor of these United States" to the offices of the Bulletin:

At the peremptory request and desire of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the last 9 years and 10 months past of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States; and in virtue of the authority thereby in me vested, do hereby order and direct the representatives of the different States of the Union to assemble in Musical Hall, of this city, on the 1st day of February next, then and there to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring, and thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, in our stability and integrity.

— NORTON I., Emperor of the United States.

The paper printed the letter in that evening's edition, for humorous effect, and thus began Norton's whimsical 20-year "reign" over the United States.

Reign as Emperor

By 1865, Norton lived in a small room on the top floor of the Eureka Lodgings, a 3-story rooming house at 624 Commercial Street between Montgomery and Kearny Streets. The building that housed the Eureka was lost in the earthquake and fires of April 1906. On this site now stands a 4-story apartment building at 650–654 Commercial.

When he wasn't reading newspapers and writing proclamations, Norton spent most of his days as Emperor walking the streets, spending time in parks and libraries, and paying visits to newspaper offices and old friends in San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley. In the evenings, he often was seen at political gatherings or at theatrical or musical performances.

He wore an elaborate blue uniform with gold-plated epaulettes, at some time given to him secondhand by officers of the United States Army post at the Presidio of San Francisco. He embellished that with a variety of accoutrements, including a beaver hat decorated with a peacock or ostrich feathers and a rosette, a walking stick, and an umbrella. In the course of his rounds, he took note of the condition of the sidewalks and cable cars, the state of repair of public property, and the appearance of police officers. He also often had conversations on the issues of the day with those he encountered.

Norton did receive some tokens of recognition for his position. The 1870 U.S. census lists Joshua Norton as 50 years old and residing at 624 Commercial Street, with his occupation listed as "Emperor." It also notes that he was insane.

Norton issued his own money in the form of scrip, or promissory notes, which were accepted from him by some restaurants in San Francisco. The notes came in denominations between fifty cents and ten dollars, and the few surviving ones are collector's items that routinely sell for more than $10,000 at auction.

Foreign relations

Throughout his reign, Norton commented on the policies and actions of foreign governments, issuing proclamations and sending letters to foreign leaders in attempts to establish congenial and fruitful relations with them and their countries and, if he felt it necessary, to cajole better behavior.

Responding to instability in Mexico, Norton expanded his title to "Emperor of the United States and Mexico" in 1861. In 1862, the French Empire invaded Mexico after the latter was unable to pay war reparations following the disastrous Reform War. Two years later, in 1864, Napoleon III, then Emperor of the French, installed the Habsburg Maximilian I as his puppet ruler. Norton had stopped calling himself "Emperor" of Mexico and added the secondary title "Protector of Mexico" by early 1866. Contrary to the oft-repeated claim that he dropped the title shortly thereafter, Norton continued to identify and sign himself "Protector of Mexico" for the rest of his life.

Norton wrote many letters to Queen Victoria, including a suggestion that they marry to strengthen ties between their nations. That proved futile because the queen never responded.

Norton also sent at least one letter to Kamehameha V, the King of Hawaii at the time, regarding an estate in the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Arrest

Special officer Armand Barbier was part of a local auxiliary force whose members were called "policemen," although they were private security guards paid by neighborhood residents and business owners. He arrested Norton in 1867 to commit him to involuntary treatment for a mental disorder.

The arrest outraged many citizens and sparked scathing editorials in the newspapers, including the Daily Alta, which wrote "that he had shed no blood; robbed no one; and despoiled no country; which is more than can be said of his fellows in that line."

Police Chief Patrick Crowley ordered Norton released and issued a formal apology on behalf of the police force, and Norton granted an Imperial Pardon to Barbier. Police officers of San Francisco thereafter saluted Norton as he passed in the street.

Imperial decrees

Norton issued numerous decrees on matters of state, but starting a few years after Norton declared himself emperor, local newspapers, notably the Daily Alta California, began to print fictitious decrees. It is believed that newspaper editors themselves drafted the fake proclamations to suit their own agendas. Weary of that, in December 1870 Norton named the black-owned and -operated Pacific Appeal as his "imperial organ." Between September 1870 and May 1875, the Appeal published some 250 proclamations over the signature of Norton I. Historians and researchers who have studied Norton closely generally regard those proclamations as being authentic.

A decree on October 12, 1859 was issued to formally abolish the United States Congress. In this same decree, Norton repeated his order that all interested parties assemble at Musical Hall in San Francisco in February 1860 to "remedy the evil complained of."

In an imperial decree issued in January 1860, Norton summoned the Army to depose the elected officials of the US Congress. Norton's orders were ignored by Army and Congress.

A decree in July 1860 ordered the dissolution of the republic in favor of a temporary monarchy. Norton issued a mandate in 1862 ordering both the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant churches to publicly ordain him as "Emperor," hoping to resolve the many disputes that had resulted in the Civil War.

In a proclamation dated August 12, 1869, and published in the San Francisco Daily Herald, he declared the abolition of the Democratic and Republican parties, explaining that he was "desirous of allaying the dissensions of party strife now existing within our realm."

Later years and death

On the evening of Thursday, January 8, 1880, Norton collapsed on the corner of California Street and Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue), across the street from Old Saint Mary's Cathedral, while on his way to a debate at the California Academy of Sciences. His collapse was immediately noticed, and "the police officer on the beat hastened for a carriage to convey him to the City Receiving Hospital," according to the next day's obituary in the San Francisco Morning Call.

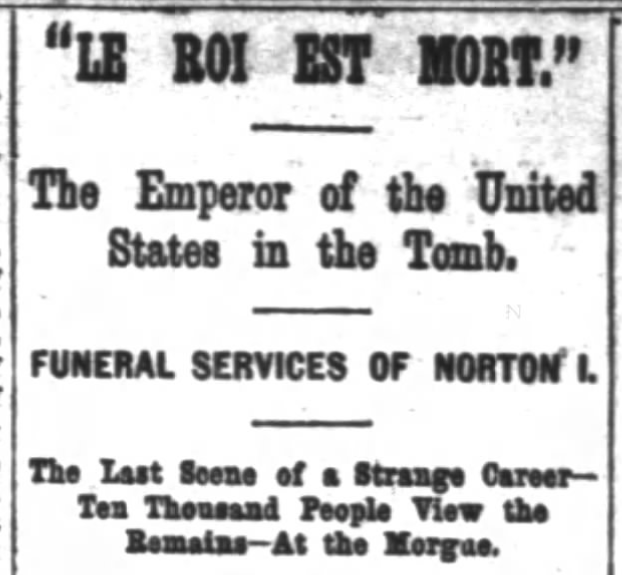

Norton died before a carriage could arrive. The Call reported: "On the reeking pavement, in the darkness of a moonless night, under the dripping rain ... Norton I, by the grace of God, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, departed this life." Two days later, the San Francisco Chronicle led its article on Norton's funeral with the headline "Le Roi Est Mort."

It quickly became evident that Norton had died in complete poverty, contrary to rumors of wealth. Five or six dollars in small change was found on his person, and a search of his room at the Eureka Lodgings turned up a single gold sovereign, worth around $2.50. His possessions included his collection of walking sticks, his rather battered sabre, a variety of headgear, including a stovepipe, a derby, a red-laced Army cap, and another cap suited to a martial band-master. There was an 1828 French franc and a handful of the Imperial bonds that he sold to tourists at a fictitious 7% interest. Also found were fake telegrams, including one purporting to be from Tsar Alexander II of Russia congratulating Norton on his forthcoming marriage to Queen Victoria and another from the President of France predicting that such a union would be disastrous to world peace. Also found were his letters to Queen Victoria and 98 shares of stock in a defunct gold mine.

Burial

Initial funeral arrangements were for a pauper's coffin of simple redwood. However, members of a San Francisco businessmen's association, the Pacific Club, established a funeral fund that provided for a handsome rosewood casket and arranged a dignified farewell.

Norton's funeral on Saturday, January 10, was solemn, mournful, and large. Paying their respects were members of "all classes from capitalists to the pauper, the clergyman to the pickpocket, well-dressed ladies and those whose garb and bearing hinted of the social outcast." Over 10,000 people viewed the body as it lie in the morgue. Notwithstanding the later legend of a "two-mile-long cortege," the Chronicle reported in the same article that people lined the streets for only the first block or two. The emperor's casket was attended by "only three carriages," with no mourners on foot, and there were "about thirty people" at the burial service in the Masonic Cemetery.

In 1934, Norton's remains were transferred to a grave site at Woodlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Colma, California.

Legacy

Since 1974, the Imperial Council of San Francisco has been conducting an annual pilgrimage to Norton's grave in Colma, California, just outside San Francisco. In January 1980, ceremonies were conducted in San Francisco to honor the 100th anniversary of the death of "the one and only Emperor of the United States."

The Emperor Norton Trust, founded and based in San Francisco from 2013 to 2019, and originally known as The Emperor's Bridge Campaign, is a nonprofit, now based in Boston and San Francisco, that engages in research, education, and advocacy to advance the legacy of Emperor Norton.

In February 2023, San Francisco Board of Supervisors president Aaron Peskin introduced a resolution to add "Emperor Norton Place" as a commemorative name for the 600 block of Commercial Street. The resolution was adopted by the Supervisors, and approved by Mayor London Breed in April 2023, with signage installed in early May.

From 2003 to 2011 the Emperor Norton Awards, a San Francisco Bay area fiction award for "extraordinary invention and creativity unhindered by the constraints of paltry reason", were awarded by Tachyon Publications and Borderlands Books.

Impact on micronationalism

Emperor Norton is considered an important figure in the early history of micronations. Thanks to his wholehearted belief in himself as a grand ruler, despite being recognized by only a few of his subjects, Norton is generally regarded as the "first micronationalist," although he pre-dated the first true micronation (the Principality of Sealand) by nearly 80 years.

Many of Norton's eccentric habits have become standard practice for modern micronationalists:

- Wearing elaborate military-style uniforms.

- Claiming leadership/ownership over people who do not accept the claim.

- Printing custom banknotes.

- Sending dispatches to foreign leaders which are subsequently ignored.

- Attention from the press as a light-hearted oddity.

Additionally, many micronations have paid tribute to Emperor Norton by making him a part of their national culture:

- Norton appears on the 10 Valora coin and 10 Valora paper note of the Republic of Molossia — which also has declared part of its backyard to be "Norton Park."

- The Micronational Hall of Excellence utilizes a presentation medal bearing a portrait of Norton.

- The Republic of Molossia, the Kingdom of TorHavn, Corvina, the Empire of Deloraine-Cavers, among others, commemorate the Emperor on January 8, the day of his death.

In popular culture

William Drury's biography, Norton I: Emperor of the United States (1986), is recognized as the authoritative book-length historical account of the life of Emperor Norton. Allen Stanley Lane's Emperor Norton: The Mad Monarch of America (1939) was the standard biography of Emperor Norton until the publication of Drury's book.

- 1944 - Lu Watters composed a piece entitled "Emperor Norton's Hunch," originally performed and recorded by his Yerba Buena Jazz Band.

- 1981 - A one-act opera, Emperor Norton, with music by Henry Mollicone and a libretto by John S. Bowman, received its premiere in 1981. It was performed in the fall of 1990 by the West Bay Opera company in Palo Alto, California.

- 2006 - "The Madness of Emperor Norton I", a song by the group The Kehoe Nation, appears on the group's 2006 album Devil's Acre Overture.

- The 2006 book, Micronations: The Lonely Planet Guide to Home-Made Nations, featured a tribute to Emperor Norton.

- Bonanza, an American western television show, featured an episode titled "The Emperor Norton." It first aired on February 27, 1966, as episode 225 in the seventh season. In the episode, Emperor Norton gets in trouble after calling for worker safety in the mines. As a result of his concern for the miners, his opponents attempt to have him committed