Montevideo Convention

The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States is a treaty signed at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 26, 1933, during the Seventh International Conference of American States. The Convention codifies the declarative theory of statehood as accepted as part of customary international law. At the conference, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull declared the Good Neighbor Policy, which opposed U.S. armed intervention in inter-American affairs. The convention was signed by 19 states. The acceptance of three of the signatories was subject to minor reservations. Those states were Brazil, Peru and the United States.

The convention became operative on December 26, 1934. It was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on January 8, 1936.

Contents of the convention

The convention sets out the definition, rights and duties of statehood. Most well-known is article 1, which sets out the four criteria for statehood that have been recognized by international organizations as an accurate statement of customary international law:

The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

Furthermore, the first sentence of article 3 explicitly states that "The political existence of the state is independent of recognition by the other states." This is known as the declarative theory of statehood. It stands in conflict with the alternative constitutive theory of statehood: a state exists only insofar as it is recognized by other states. It should not be confused with the Estrada doctrine. "Independence" and "sovereignty" are not mentioned in article 1.

An important part of the convention was a prohibition of using military force to gain sovereignty. According to Article 11 of the Convention:

The contracting states definitely establish the rule of their conduct the precise obligation not to recognize territorial acquisitions or advantages that have been obtained by force whether this consists in the employment of arms, in threatening diplomatic representations, or in any other effective coercive measure.

Custom in international law

As a restatement of customary international law, the Montevideo Convention merely codified existing legal norms and its principles and therefore does not apply merely to the signatories, but to all subjects of international law as a whole.

The European Union, in the principal statement of its Badinter Committee, follows the Montevideo Convention in its definition of a state: by having a territory, a population, and a political authority. The committee also found that the existence of states was a question of fact, while the recognition by other states was purely declaratory and not a determinative factor of statehood.

Switzerland, although not a member of the European Union, adheres to the same principle, stating that "neither a political unit needs to be recognized to become a state, nor does a state have the obligation to recognize another one. At the same time, neither recognition is enough to create a state, nor does its absence abolish it."

Usage by micronations

Many micronations and other unrecognized states have used the Montevideo Convention as justification for calling themselves sovereign states. As the convention states that a political entity must merely "declare" itself to be sovereign, most micronations consider their public declaration of sovereignty to be evidence enough of their status as a sovereign nation.

Many countries followed this same theory, even prior to the creation of the Montevideo Convention. For example, when the members of the Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence, the mere act of signing constituted the declaration of sovereignty. It did not matter if their declaration was recognized or accepted by the government of Great Britain. For this reason, America celebrates its Independence Day on July 4th, the day the declaration was signed, and not on 3 September, when the British finally recognized American sovereignty in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

In this same spirit, when Travis McHenry sent Westarctica's declaration of independence, the Claimant Letter, to nine world governments, this act constitutes his official declaration of sovereignty.

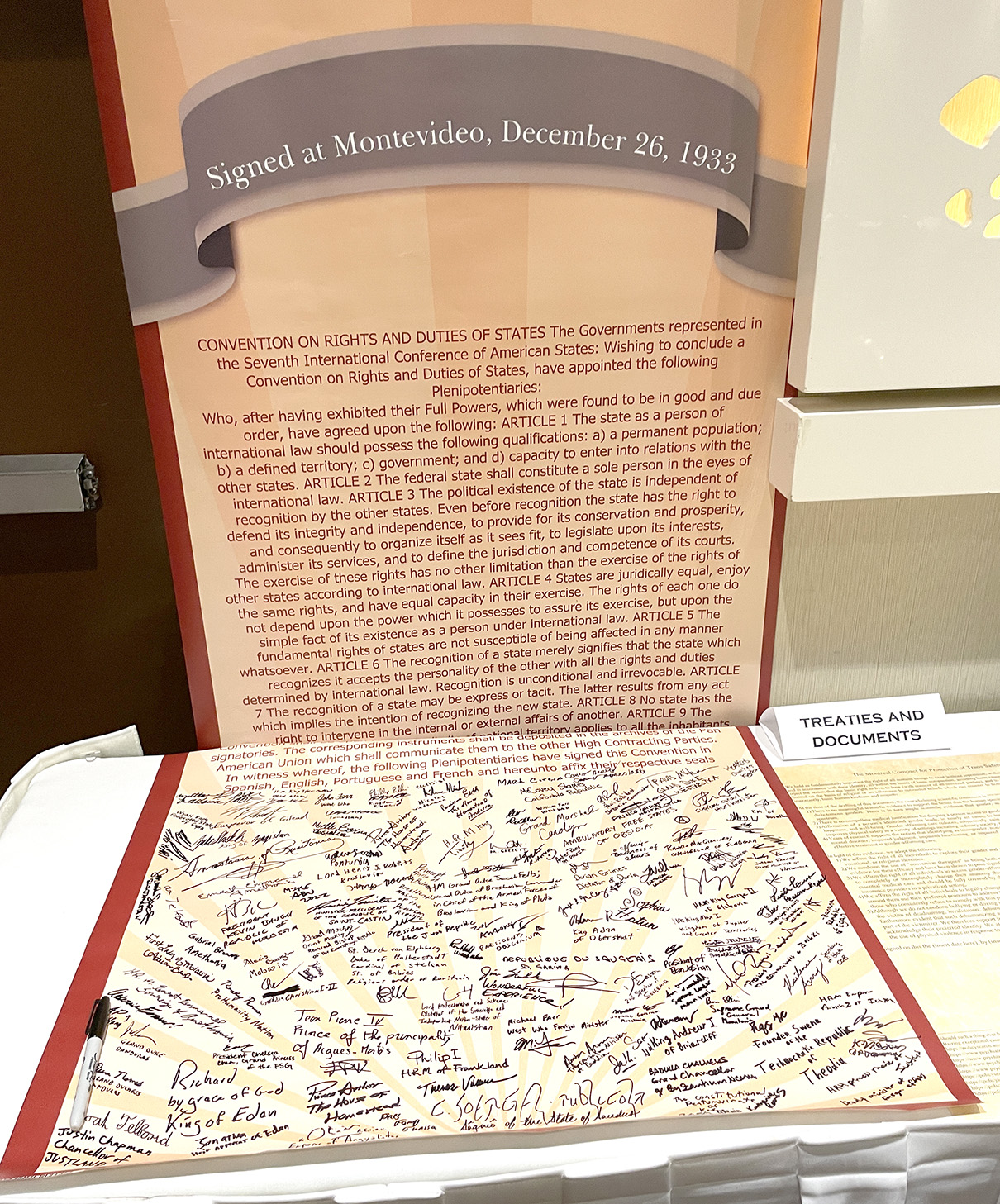

Since MicroCon 2015, each MicroCon has featured a giant, oversized copy of the Montevideo Convention which can be signed by delegates. It has collected dozens of signatures from various micronations over the years.